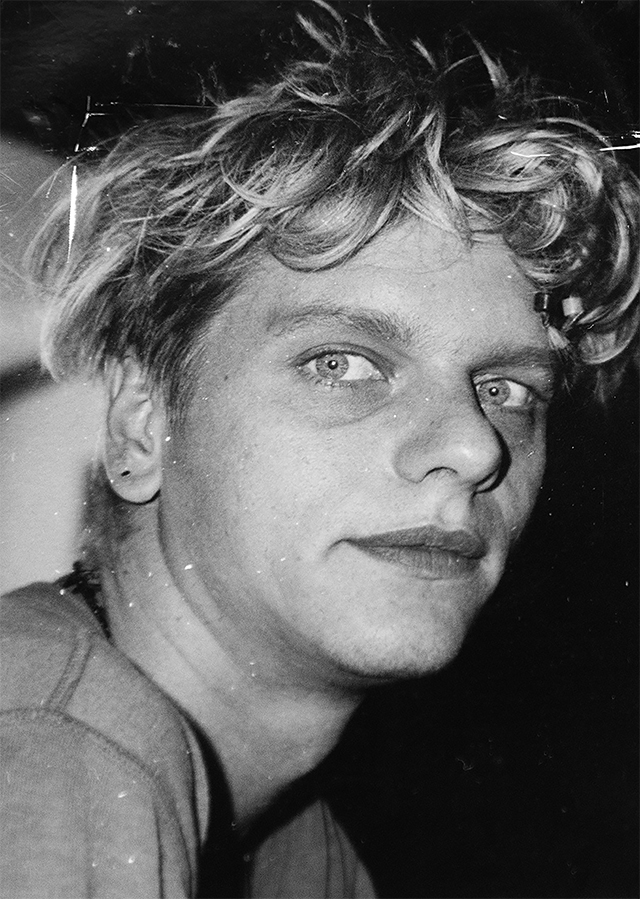

André

André came to the city from the West German provinces with colourful hair and lots of punk cassettes. And he left again with punk in his heart. André and Markus invented the Pyonen, the crew made it what they are today. Party organisers, trailblazers, reality escape helpers.

André died in 2020. For the Pyonen, it is impossible to forget André. For the others, we want to tell his story here. Not only because he was a particularly empathetic person, but also because he shaped the self-image of our party culture as a synergy-seeking scene, as a utopian event, and would certainly continue to do so.

When he came here, he lived with Markus and other friends in a house in Rykestraße, where there was no heating, no telephones, but plenty of space to fool around. They held their first party in 1993 at Lychener Straße 60. Sven Dohse was the DJ and Gianni Vitiello came by at some point and asked if he could DJ.

So it happened that years later he played in front of thousands at the Carnival of Cultures, when the Pyonen drove through Kreuzberg with a truck full of boxes as part of the parade. They turned empty buildings into clubs for a night. Opened an illegal club in Schlegelstraße in Mitte, which was open from 1996 to 1998, first in the basement, then in other parts of the building.

In 2001 they opened their first bar in Prenzlauer Berg, Bar23. They also run pubs like Tante Liesbeth, Fetten Ecke and Böhmisches Dorf, complete with bulky waste-like furnishings that André lovingly bought together at flea markets. There he liked to sit at the bar as a tippler, beer dispenser, Union fan, gossip box and gossip.

André and Markus were among the first to organise open air raves. From 1995 onwards, they celebrated a small festival on a horse meadow, which they called Nation of Gondwana. The Nation established itself as a Love Parade alternative. But instead of just dissipating in escapism, from 1999 they organised and produced the Chaos Computer Club camp, where they taught party aesthetics and a sense of community to the hackers and in return brought the party people together with the utopians.

All his knowledge André was happy to share. He always had advice, sometimes unsolicited. But most of the time he was even right. Who is good at working with metal? Who makes good awareness concepts? Which loudspeakers are suitable for a techno parade? He gave the right keywords on the phone, forwarded e-mail addresses.

André also kept in firm contact with Grünefeld, the place where the nation settled down. As a boy from the north German province, he knew how to bowl, hold warm-hearted banter and make dry jokes. The festival supports local clubs, donates to the kindergarten and integrates local residents who offer food or shower guests in the drizzle with the volunteer fire brigade.

André, who among other things took care of the booking at the Nation and listened to endless amounts of music in return, however, mostly liked to watch the goings-on from further afar. For hours he sat on a sofa in silence, smoking, beer in hand, and watched the dancers with a grin. Now and then making a precise comment. Unabashedly honest, always full of respect.

Because he had convictions. Work with security guards who train in right-wing boxing clubs? Better to use anti-fascist structures. Women at the door and at the DJ booth? Of course. Securing woodland to convict a peeping Tom, yeah right. Collecting cigarette butts from the meadow, doing without sponsors and making the calculation transparent in order to explain extensively on Facebook why the festival ticket was more expensive. That was important to him. But he didn’t make a big deal out of it.

André died at the age of 52. Of a cancer he managed to fight for much longer than many a doctor had thought.

“Never give up and believe in yourself”,

that was his motto. And it remains ours.